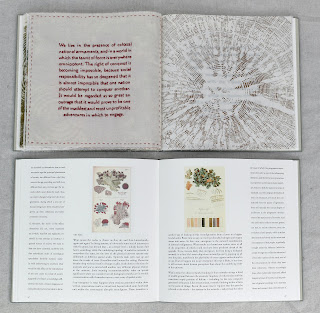

Two volume artist’s book in clamshell box. A study of lichen as a system, and of society as a system: a lens for examining how the organism requires thinking and acting beyond the immediate needs of the individual.

Hand painted wood veneer covers [designs vary], 6 hand embroidered pages, 8 woodcut prints, 6 woodcut collages digitally printed on fabric, and two essays: Twelve Readings on the Lichen Thallus by Trevor Goward, and A System of Logic by John Stuart Mill, with historic lichen imagery. The hand-embroidered pages are the text from the Sociology entry of The Encyclopaedia Britannica 11th edition, which describes society as a organism working towards the health of the whole over the desires of the individual.

9"x 9". Limited edition of 10. Two volumes in clamshell box. Ships 7/15/2022.

In the early autumn of 2021, I became fascinated by the unresolved nature of the definition of lichen: how it is a combination of algae and fungus, and how it forms a third, completely different organism than would be possible without this combination, and how science is still rather flummoxed by many of the characteristics of it: is it an organism? Is it mostly a fungus? Is it a parasite? Is it mutually beneficial? Different scientists have different interpretations, and it was only at the invention of more powerful microscopes in the late 18th century that Erik Acharius teased out the component parts. I was also interested in their functionality: the time scale they operate in, by the climates they grow in, how they display interdependence into a new whole.

One of the books about lichen that I most enjoyed was Kem Luther’s book “Boundary Layer,” which including a reference to the work of a Canadian scientist, Trevor Goward, who wrote a series of essays entitled Twelve Readings on the Lichen Thallus. These personal essays combine science with storytelling to explore the nature of lichens, and come to the conclusion that they can best be experienced as systems rather than as individual parts acting in self interest. Trevor Goward very kindly gave me permission to reprint his essays, which I abridged in the desire to tell the story that interested me: the story of a system formed of interdependent parts.

This led me to start searching for other metaphor that explored the nature of systems: what would make lichen something that other people could conceptualize, who weren’t already knowledgeable? What would make lichen larger than a biological curiosity? I started looking into other examples of networks and systems: neuroscience, brain theory and the nervous system; transportation hubs; samples of manufacturing using unexpected materials; and then, while using google books and the internet archive and searching using the term “system theory,” I came across John Stuart Mill’s book which established social science, A System of Logic.

This is, honestly, a very long book that spends a very long time talking about the nature of logic and the establishment of scientific norms, but, once you are through all the introductory matter, there is a compelling section that applies the nature of logical thinking to the study of human rights and society — in short, the establishment of sociology as a field — the study of humanity and politics as a system.

The text of the book is the abridged essays by Goward; the borders of the pages have the abridged text of Stuart Mill. Throughout the book, imagery from the early scientists has been brought into the page designs: the botanical illustrations of Acharius, Nageli, and Westrings.

The same way that volume 1 has three disparate elements [algae, fungus, cyanobacteria; Goward, Stuart Mills, historic botanical plates], so does volume two: embroidered text, woodblock prints, and digital collages.

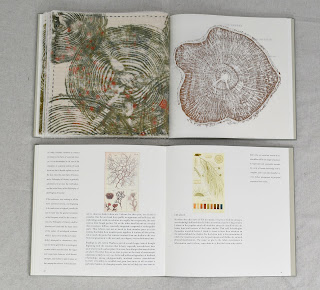

Volume two of the book uses a more poetic exploration of the visual nature of lichen, combined with the most laborious and slow-growing method of creating text on the page that is possible — hand embroidery.

Combining materials, paper, wood, fabric mirrors the way that lichen is a plant-like growth on rocks and trees — and inspired by the fabric books of Louise Bourgeois for inspiration in how cloth could work as a book structure. [New York Times | MoMA [original] | [edition] ]

I was interested in incorporating a woodgrain print element to the project, based on the photograph from the nature hike [above] with the lichen growing on a felled trunk. The first step was to explore how to create a print from a piece of wood. There was a great online forum of Canadian woodworkers who had a conversation where sanding the wood smooth and then using a wire brush drill attachment to pull out the soft grain so that the rings would form prints. My studio was partitioned into a special sanding area (plastic cloths hanging from the ceiling) and sanding and wire-brushing commenced.

These sanded blocks were then turned into rubbings using graphite on paper, then dropped into Photoshop, and digital collages were made using the rubbings and the hand-dyed covers [see below]. The resulting collages were then digitally printed onto organic cotton, which was then dyed in the studio in a bath of acorn dye [acorns collected by my nephews over Thanksgiving], then cut down into panels for the books.

Embroidery was always a foundational part of the conception of this project: it is text literally growing on the substrate, the way that lichen grows on trees and rocks, and it is slow, remarkably slower, slower even than calligraphy or using handset type; it operates at the scale that lichen grows. It took me some time to develop how I wanted the embroidery to work with the woodcut collages: I wasn’t certain what text or imagery was most appropriate, but remembered that I had a copy of the famous Encyclopaedia Britannica 11th Edition, and the article on Sociology fit in cleanly with the message that I sought through volume one:

It is a feature of organisms that as we rise in the scale of life the meaning of the present life of the organism is to an increasing degree subordinate to the larger meaning of its life as a whole. The efficiency of an organism must always be greater than the total of its members acting as individuals.

I extracted a total of six excerpts from the text, which narratively illustrate this concept of the sum being greater than the parts. After each pane was embroidered, it was trimmed with a rough edge, formed into signatures with a second embroidered panel and two collages, and the outer edges were stitched, in pursuit of the softer edge finish this provides.

Bringing the woodcut element into sharper relief, inked woodblock prints were created by printmaker Catherine Ulitsky, who accompanied me on the lichen walk through the Hawley Bog pictured earlier. In addition to being a trained professional printmaker, Catherine also has a long history of interest in the natural environment and our relationship with it, and her selections of woodblocks and thoughtful inking bring a sharp visual focal point into the edition, providing a foundation for the embroidery and collages to grow in relation to.

The covers of

the books are maple veneer panels, hand dyed in a range of colors and

patterns to resemble the various palettes and forms that lichen takes,

on trees and on stones. Each cover is different; while the covers of

volume one and volume two are in relationship to each other as far as

tone, it was never the intention to have them match or coordinate.

Nature is too diverse for me to be interested in that as a solution. A

selection of these panels were used as a base and color layer for the

digital collages of volume two.

The same way that lichen is a

relationship between disparate elements that forms a complex, functional

system, this book incorporated the skills and talents of a group of

people that I am thrilled were graciously involved in the project.

Without Trevor Goward’s essay, Catherine Ulitsky’s woodblock prints, and

the talented handcraft of my studio assistant, Kayla Mattes, this

project would not have unified into the whole presentation that it

offers the reader.