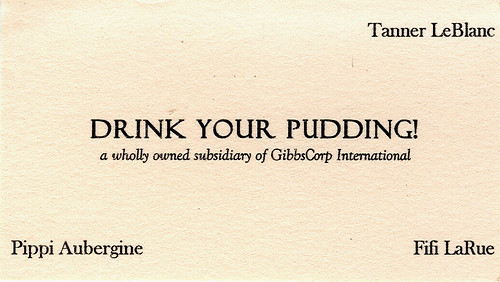

This rather summarizes the year: an upside-down pane, noticed two days after the cards were mailed. How many were affected? Who are the recipients of this bibliographic irregularity (and hopefully rarity)? When I say my concentration has been shattered to pieces, this neatly encapsulates the result...

Wednesday, December 9, 2020

Monday, December 7, 2020

living in liminal spaces

2020 marked my five-years-in-Los-Angeles anniversary, and the traditional gift for this milestone is wood. Hiromi Paper carries a stock of paper-wood (wood veneer) products, and I’d been curious about using them for printing and foil stamping, so this year’s edition started with the desire to incorporate wood in some format.

As I cycled through the maelstrom of the year, I struggled to anchor in the present tense. It’s a difficult task for me at the best of times; I tend to live three steps in the future, and suddenly the future was too foreign, and the present too fraught. One of the books I read this year introduced me to the Buddhist philosophy of time as linked moments, rather than a progression, as explored by the Zen Buddhist teacher Dogen in his essay on Being-Time. This was a useful reminder, to value the present moment as a moment, rather than looking at either the moments that didn’t happen, or the moments that have not yet happened. I really liked the translation by Thomas Cleary, but the one by Dan Welch and Kazuaki Tanahashi is a bit easier to parse.

Do not think that time merely flies away. Do not see flying away as the only function of time. If time merely flies away, you would be separated from time.In essence, all things in the entire world are linked with one another as moments. Because all moments are the time-being, they are your time-being.

Practice-enlightenment is time. Being splattered with mud and getting wet with water is also time.At this point, I had the material (wood veneer) and the text (Being-Time), and I started to think about format. Knowing that this year’s text was from Buddhist philosophy and has a rigid material as the substrate, the format of the palm leaf book was immediately apparent as being most appropriate. Palm leaf books are traditional to southern Asian religious texts, and often incorporate calligraphy with small ornamental flourishes; there are some great tutorials online: I especially liked this one from the University of Iowa. Additionally, an early western essay was available from JSTOR, which provided a interesting look at the bibliographic interpretation of the format in the west. That my adopted city of Los Angeles is awash in palm trees adds to the appropriate nature of this format.

The text had a tendency to rub off of the paperwood, so I did three tests with different fixatives: PVA size, matte medium, and klucel-g (a conservation consolidant). They helped fill in the grain of the wood, but then needed to be buffed with sandpaper and steel wool. And then they actually printed even less well on my home printer: thankfully they printed beautifully on commercial printers.

After printing, the sewing stations were stamped in red foil; then the paperwood was backed with a decorative Japanese paper. They were then punched for sewing, then cut into individual staves.

I wasn’t sure what type of sewing method would be the most stable; after a few tests, knotting the thread between each stave helped keep everything in alignment. While I liked the frivolous nature of the gold thread, it was significantly more brittle than the red thread, and tended to break during the sewing process. Looping the ends as an extension at the top allows the books to be hung, like a broadside.

And so, folded against themselves, wrapped, and posted, they fly into the final days of what has been a year of turmoil, and a year for trying to hold onto the smallest of moments, of catching my breath and breathing deeply, in and through the uncertainty of what has been and what will be.

further thoughts of

Stephanie Gibbs

at

9:15 PM

![]()

Tuesday, October 27, 2020

this year, it's virtual

While I am the first person to admit that I don't remotely enjoy the performative aspects of art fairs, they are a useful benchmark for keeping track of the passage of time -- in my studio life, days run into days run into days, and I'm never quite sure if a week has passed, or six months, or three years. The Los Angeles Printer's Fair is always a particularly sentimental occasion for me (rather than a particularly professional one), since it is the benchmark for my anniversary of relocating to Los Angeles, and I'm extremely grateful for the landing pad that the International Printing Museum provided upon my arrival. Since fairs aren't happening this year, the LAPF2020 is being held virtually, and I agreed to make a series of short videos as part of their multimedia presentation.

My preferences for technologies are for the outdated and the obsolete; while I'm not a Luddite, I'm also not a technophile. They offered to lend me a professional videographer for the project, but since I closed my studio to the public seven (?!?!?!?) months ago, it didn't seem appropriate to have someone in the space for an extended period of time, while I narrated sans mask. As a result, I cobbled together a narrated series of instructions using my phone and the software on my laptop.

You'll notice that: my hands look exceptionally awful, even by my standards. They're covered in burns from foil stamping, and they're covered in scratches from PandemicKitten™ Vincent. Also, these particular structures are (a) the ones that I generally teach in introductory workshops, and (b) ones I've used in recent Holiday Editions, so I had samples readily available. You'll also notice that I didn't use a pre-written script, and as I was recording the narrations, I was drinking wine. So there's a bit of narrative ... irregularity, repetitiveness, and inaccuracy. At no point do I actually go off the rails, which, to be honest, would have been more interesting.

The resulting four videos will appear wherever the LAPF multimedia extravaganza is being posted; presumably on all the usual sites. I don't know if they'll ask me to provide additional content to help fill space. Nature abhors a vacuum, but I would also argue that people abhor amateur multimedia content. These were created with an audience of absolute beginners in mind, and feature such bookbinding materials as Glue Sticks and button thread.

Rather than drip them out one at a time, I'm posting all of them here, together, since that will make archiving them easier. They can also be found directly on youtube, here.

Introduction

Cut and Fold Booklets

Accordion Books

Sewn Signature Pamphlets

If you make something as a result of these instructions, please do send me a photo. I love seeing other people's projects!

further thoughts of

Gibbs Bookbinding

at

6:50 PM

![]()

Sunday, June 7, 2020

Waterways

The installation, which we have been referring to as "The Vertigo Lounge," takes its name from Akomfrah's three-channel film, Vertigo Sea (2015), that explores the ocean's beauty in our current moment on the verge of climate crisis. In this installation, which is situated in the final gallery of the exhibition, we have included several artist's books that address or reference climate change, a book shelf of climate- and Akomfrah-related titles, a short film about the herring spawn in Sitka, AK, and an interactive element that encourages visitors to record their ideas about ways to save the planet.The exhibition and installation opened in February, but was closed in March due to the coronavirus pandemic. In lieu of this, the curators of the Akomfrah exhibition are going to do a recorded presentation for SAM at the end of July. That link will be provided as it becomes available.

- Why did you decide to focus your work on water/water scarcity?

- Tell us about the process of making Between, Among, Within. How did you decide on the images?

- What do you want a reader to take away from the work?

- Since the COVID 19 pandemic, have you thought about this work in a different way?

The following reflections are on the creation, intention, philosophy, and evolution of thinking as pertains to my artist’s book, Between, Among, Within, which was created in 2016 using new research and re-incorporating prior work.

Why did you decide to focus your work on water/water scarcity?

In all of the places that I have lived, I’ve been keenly interested in the interplay between systems for sustaining the delicate balance between human life and environmental balance. Water is a particularly noteworthy barometer for how humans view resources. Water, itself, cannot be created or destroyed. It evaporates; it forms clouds; it rains. It falls into the seas; it falls on land; it absorbs into aquifers. Humans dig wells, then dig deeper wells, then drill into aquifers, then use the water from aquifers without any consideration for the recharging period necessary for water to leech back into the underground system. In Texas, where I grew up, water is a privately owned commodity, like oil or stone. Entire towns in Massachusetts were in protracted legal fights with the Coca-Cola company about losing their water to bottling plants; inevitably, as corporations have deeper financial resources than small towns, the towns run out of money to continue to the fight. Internationally, the problem is even worse.

When I was living in Boston, the city was reconstructing Washington Blvd (which ran through my neighborhood), and part of the public works project was replacing the original water pipes of the city: hollowed out logs. After I moved to western Massachusetts, I learned that all of the water consumed in Boston came from flooding several towns in the central part of the state in order to create the Quabbin Reservoir. Entire communities were destroyed, families forcefully relocated, and a public works flooding project engineered in order to provide for “the greater good.” They didn’t even de-construct the towns: when the water level in the reservoir drops, rooftops of the buildings can still be seen, and the original roads have been left as restricted access hiking paths. The politics of the use policies of the Quabbin were equally perplexing. No swimming, no kayaking, but motorboats were fine. Which is going to pollute public drinking water more? A gas powered motorboat or a hand powered canoe? Which has more political power, sportsmen or kayakers?

In 2015 I relocated my home and studio from rural western Massachusetts to central Los Angeles. The first thing that I noticed was how parched the air was: the pervasive dryness was a genuine shock. The state was coming off of a prolonged drought; the reservoirs were emptied, or being covered in floating black balls to prevent evaporation; the city was aggressively paying residents to tear out water-hungry lawns and emphasize native, drought-tolerant plants. I felt guilty if it took longer than three minutes to shower. I washed dishes in as little water as possible. When working, I had to completely re-calculate the moisture content of my glue and working time. Projects dried faster, glue dried faster, paper was more brittle, leather reacted differently.

None of this should have been a surprise. I moved to California partly to be in a drier climate. I grew up in Texas, where summer temperatures regularly reach above a hundred, and I have many childhood memories of summer droughts in Texas in the 1980s, with watering restrictions and fireworks regulations in place. I knew that Los Angeles was experiencing an historic drought; I knew that water levels in the Colorado River were so low that the river no longer flowed to the Pacific Ocean; I knew about arid climates and dry seasons. But knowing and experiencing are two entirely different things; I suddenly felt the lack of water, in a way I never had before. The situation in Los Angeles, an arid city reliant on water from the mountains, a city whose boundaries have been shaped as the city annexed land in order to secure water rights, have best been illustrated in the movie “Chinatown,” which, while not a documentary, shows the extreme powers at play in the situation. I watched as the Silver Lake reservoir was emptied; as wealthy homeowners fought to have it re-filled instead of an empty concrete basin; as a water-bottling company donated thousands of gallons of “expired” bottled water to refill the reservoir. This perverts the water cycle to: rainfall in the mountains; bottling by a private company; donation of water as an aesthetic accessory to wealthy neighborhoods.

And I live in an active earthquake zone. Through all this, I have approximately ten gallons of water squirreled away around my apartment. I check it annually and replace it every two years. I hope I never need to rely upon it. I’m terrified that I will.

Tell us about the process of making Between, Among, Within. How did you decide on the images?

The pastepapers were created in the summer of 2009 for an unrelated and uncompleted artist’s book edition about language and omission. Two editions of the pastepapers were made: indigo pigment in paste on white (machine, western) paper, and indigo pigment in paste on black Japanese paper. Both of these variations are represented in the final Between, Among, Within project. After finishing the prototype, the pastepapers were put into storage and the project languished.

When I began work on the project that became Between, Among, Within, I started by going through my archive of unused project pieces, and separating out those that I thought could be meaningfully re-imagined as new pieces. Looking over the pastepapers, I drew up a list of visual metaphors: flying buttresses, cathedrals, rivers, bridges. Then I began to look for imagery that magnified the interpretations of the patterns. I was thinking quite a lot about waterways, water rights, and rivers; discovering that the entire construction of the system to bring water to the city of New York from upstate had been photo-documented was exciting. I would have preferred to use images that more specifically related to a place that I lived; but I could not find comparable imagery for California, Texas, or Massachusetts.

The photographs were sourced from the New York Public Library historic photography collection, illustrating the construction of the water supply system to transport water from upstate (the Catskill Mountains) to the City in the early years of the twentieth century (1917/1928). What I liked about these photographs was not only the architectural shape of the scaffolding, tunnels, and bridges, but how much they emphasized the human element of the construction. There are men with shovels, men with rail cars, men working. The individual stories of these men have been lost to time: I doubt any statistics were kept as to how many men died working on the project. Presumably state records would indicate whether they were paid laborers or if prison work gangs were also used; what they were paid; how many hours per day and days per week they had to work. This was before the era of the union: and while the resulting structures may be both beautiful and useful, there is rarely an accounting of the human cost of the creation. As a bookbinder, I am deeply attuned to the presence of hand-work towards a completed product; as I consider the history of the industrial revolution and the changing attitudes towards “labor” and “work”, I am eager for the visible residue of human hands on construction projects of a massive scale.

The inclusion of a map showing the natural path of the waterway was equally integral to the project. Water flows from high elevations to lower elevations; water flows from the mountains to the sea. However, it does so in a pattern that, quite literally, meanders, creating oxbows, eddies, and rapids. The end result of the path may be the same, but the entire ecosystem and shape created by the will of the water is distinctly different. Nature has a path, and it is not the road of man.

The sine curve chosen for the cover stamping, in lieu of lettering the title, provides a geometrical metaphor for rising, falling, and cycling; not the movement of wave theory, but the back and forth as an equilibrium is sought.

What do you want a reader to take away from the work?

I do not have any particular expectations for the reader of the work. Some will find meaning in the shape of the pastepaper patterns; others will be fascinated by the photographs. Many readers miss the map component altogether. I would like the pastepapers to function as the connecting waterway through the construction of the systems, flowing the reader downstream, and providing pauses between the images for the mind to reset before it take on new information. I’d like the readers to think about pathways and to think about intentions, and to think about the layers of costs, human and environmental, of shaping nature and of supporting human life.

Since the COVID 19 pandemic, have you thought about this work in a different way?

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, and the racial justice protects that have accompanied it, I’ve been thinking about the distinctly American philosophies that underpin the way we treat our environment, the way we treat our fellow humans, and the role that we allow the government to play in enacting these beliefs. The complete re-routing of a watershed system across a state, an “inconvenience” to a few and a rebuilding of nature, was deemed essential by urban planners in the early twentieth century. There was no small amount of loss associated with destroying entire communities and changing the flow of rivers, but the need to support human life on a larger scale was deemed of higher importance. The system pictured in these photographs predates the 1918 flu, and the expansion of the system predates the 1930s depression; this serves as an indicator for what governments can accomplish when the will power exists. This was all done on a state level, with federal funds and support.

What I see is a system where there is no political will to take care of the lifeblood of a population. There are National Guardsmen with machine guns posted underneath the windows of my studio. Last week the entire intersection under my windows was full of tactical police in riot gear rerouting peaceful protestors through aggressive means. I moved all of my clients’ work out of my studio and to my apartment because I’m terrified of arson. I’m also terrified of tear gas.

Now imagine a different outcome. Look at the political will that created lakes, that rerouted rivers, to provide water to cities across America. Imagine if instead of insufficient $1200 one-time allowances from the government, people were given an amount of money that actually covered the cost of rent. Imagine if instead of publicly traded companies scooping government loans, that money actually went to the many small businesses and independent contractors who have had difficulties getting their applications approved. Imagine if instead of billionaires and congressmen selling off stocks at the start of the pandemic that grocery store, warehouse, and slaughterhouse workers were paid not a minimum wage but a living wage. Imagine if in the middle of a major medical pandemic people’s health insurance wasn’t tied to their employer, as businesses are laying off employees and closing. Imagine if instead of police officers being funded to purchase military gear that medical workers had all the PPE they required to not die while saving lives.

We live in a country with great resources and great willpower. We have the ability to envision a different outcome, to plan the pathway to achieve that goal, and to put forth the effort for the vision to become a reality. Imagine if physical health, economic security, and racial justice was given the same importance as water.

further thoughts of

Gibbs Bookbinding

at

12:39 PM

![]()